한식 읽기 좋은 날

Vol 51. Korean Food that comes from trees

Let’s learn about Dano

Facts about HANSIK

In the past, Koreans spent one day in the period between spring and summer praying for a plentiful harvest and generally having fun. As with any festive occasion, Dano would not be complete without its delicious foods. Let’s learn more about Dano through the foods eaten on that day.

Article by Cha Yeji (Editorial Team) Sources Gangneung Danoje Festival Committee, Encyclopedia of Korean Culture, Korean Culture and Information Service

What does “dano” mean? What did people do on Dano?

Dano is celebrated on the fifth day of the lunar year’s fifth month by holding a ritual, after the rice has been planted in the paddies, for a plentiful harvest. According to traditional belief, odd numbers were regarded as yang (the sun, good). Dates made up of two odd numbers (third day of the third month, fifth day of the fifth month, seventh day of the seventh month, and ninth day of the ninth month) were regarded as auspicious and days on which one could do anything and not fail. This is why Dano, which is one of these dates, was an especially festive celebration featuring various games.

The biggest Dano activity, called danojang, was the washing of hair with iris-infused water. Iris water was believed to make hair glossier and prevent hair loss. Shin Yun Bok’s Scenery on Dano Day is the most well-known painting about Dano. In it, you can see several women, some of whom are washing their hair at a stream, while another is getting onto a swing. The swing is interesting because it was one of the few ways in which women at the time could enjoy the outdoors outside of their home.

Korean Traditional Wrestling by Kim Hondgo portrays men wrestling—a game that was enjoyed on other holidays as well. Today, experts believe that wrestling became associated with Dano because of the latter’s celebration of health and abundance at a warm time of year and the perception of wrestling as an expression of physical virility.

Why is Dano not celebrated widely today?

It is true that, due to the dwindling rural population in Korea and the subsequent decrease in interactions among villagers, Dano is not celebrated by as many people as it used to be. There are still, however, those who strive to maintain the traditions of this warmweather holiday. Each year, the Gangneung Danoje Festival is held in Gangneung, Gangwon-do Province, with activities (e.g. offerings to heaven, shamanic rituals, mask plays) designed specifically to preserve the Dano tradition. Preparation for Dano began on the fifth day of the fourth lunar month by brewing liquor with rice and yeast.

After people conducted rituals praying for a good harvest, five days in the fifth month (third to seventh day) were devoted to shamanic rites and various other activities. On the evening of the seventh day, the last rite, called “Songsinje,” is held, at which the paper flowers, boats, dragons, and other objects used throughout Dano are burned.

Ⓒ Gangneung Danoje Festival Committee

Ⓒ Gangneung Danoje Festival Committee

What do people eat on Dano?

On Dano, people ate food that was believed to dispel evil energy from the body and restore the body’s positive energy. Examples include surichwi tteok, aengdu hwachae (punch), aengdupyeon, jehotang, and junchi-based dishes.

Surichwi tteok (pictured) is a rice cake that is strongly associated with Dano and made with surichwi, a nutrient-packed plant that grows at high elevations. The name is derived from the pure Korean word for Dano, “Suritnal.” Because “suri” sounds similar to the Korean word for wheel (surye), the rice cakes are stamped with a wheel design.

Aengdu is a cherry-like fruit that is in season at around the time of Dano, which inevitably led it to be used for several of the holiday’s most well-known dishes. Aengdupyeon (pictured) is a jellied snack made by boiling ripe aengdu, squeezing juice from it, and then boiling down the juice after adding honey. The “secret” is to add starch to the juice, which makes the juice harden into a firm, jellylike substance that is then sliced into rectangular pieces. Aengdu was often used for Dano and foods served on other holidays because of its taste and beautiful red color. In pre-modern Korea, aengdupyeon was enjoyed not only for Dano but also frequently featured at royal banquets.

Jehotang (pictured) is a beverage that is an especially effective thirst-reliever. It is made by first making a powder of various medicinal ingredients (omija, ginseng, etc.), boiling this powder in water, and then cooling it. (Honey can be added based on preference.) Because jehotang contains so many beneficial ingredients, it was regularly served to the king. Jehotang was consumed on Dano to protect the body from the early summer heat. Indeed, it was so well-liked that people said drinking jehotang all summer long, starting on Dano, would protect the person from burning up in the heat!

Junchi is a white-fleshed fish in the Clupeiformes family that lives in deep waters. To survive the pressure of such deep waters, junchi’s flesh evolved to become very solid and, therefore, rots much slower than that of other fish. It is this quality that is behind the saying “Even if it rots, it is still junchi,” meaning that even if something valuable is old or has spoiled, its value has not diminished.

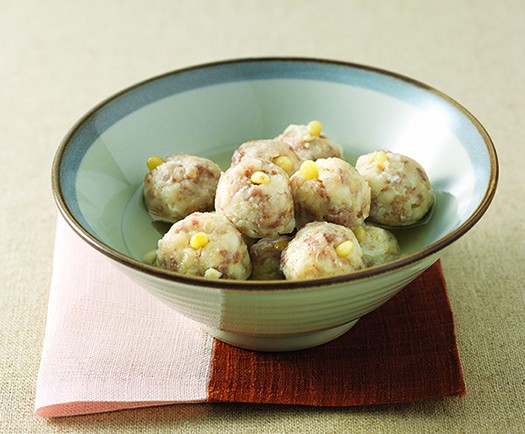

The two main Dano dishes made with junchi are junchitang (soup) and junchi mandu (dumplings; pictured). Junchitang is a clear soup that is topped with fish balls (wanja) made with junchi flesh. Junchi mandu is made with a filling of junchi and beef and no wrap. The shape of the dumplings is maintained by coating them with a thin layer of starch. Junchi is also healthy because of high protein content.

Surichwi tteok

Aengdupyeon Ⓒ Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

Jehotang Ⓒ Korean Culture and Information Service

Junchi mandu Ⓒ Rural Development Administration

한국어

한국어

English

English