한식 읽기 좋은 날

The Roots of Hansik, Home-Cooked Meals

HANSIK's Space

At the heart of Hansik's global popularity is zipbap, the home-cooked meal that embodies the warm and humane nature of the Korean people. The steaming rice served with every meal encapsulates the sincere heart of its server, while each side dish meticulously arranged on the table reflects heartfelt effort.

When eating together gathered around a warm home-cooked meal, we not only satiate our appetite but also learn the values of humanity and life's wisdom. The sense of fullness one feels when eating and sharing zipbap together originates from the desire to feed the family abundantly and to share the beauty of tastefulness.

Bap: A Meal that Asks About Your Well-Being

In Korea, the question “Did you have bap?” holds much more significance than its literal meaning. Bap literally means ‘rice’ and, more broadly, ‘meal’. When someone asks if you had bap, they aren't simply inquiring if you ate rice; it's a form of greeting that asks about your well-being. The importance of rice in Korean culture is so profound that eating rice has become a key indicator of one’s welfare. Even in an era where people can easily enjoy delicacies from around the world, it is evident that the strength that sustains Koreans is rooted in rice.

The essence of Hansik lies in home-cooked meals, where life begins and communal norms are learned around the dining table. It is said that during the Joseon Dynasty noblemen would not consider it a proper meal, no matter how lavish the feast, if they were not served a combination of rice, soup, and side dishes. Even today, it is customary to offer visitors to one’s home a warm meal before they leave. As such, Korean home-cooked meals are beloved based on the warm-hearted sentiment of showing respect and care for others' well-being.

A History of Korean Zipbap

Korea, with its natural environment of lush mountains, dense forests, and being a peninsula surrounded on three sides by the sea, has four distinct seasons and climatic differences across regions. As a result, diverse food resources have been produced in each region since ancient times. Thanks to this, methods for deliciously consuming vegetables and seaweed and the development of various regional dishes utilizing diverse ingredients have evolved.

The everyday meals of Hansik are fundamentally composed of bap (rice) as the staple and banchan (side dishes) as accompaniments. Depending on the number of banchan, the meal is classified into anywhere from a 3-cheop to a 12-cheop meal. Even a simple 3-cheop meal features a harmonious balance of various ingredients and nutrients. Side dishes are typically selected and combined from categories such as kimchi, saengchae (fresh vegetables), sukchae (cooked vegetables), gui (grilled dishes), jorim (braised dishes), jeon (pan-fried battered dishes), hoe (raw fish), jeotgal (salted seafood), and dry side dishes, ensuring that the same cooking method and ingredients are not repeated.

Since when did serving meals composed of bap (rice) and banchan (side dishes) become a common practice? According to historical documents, this practice likely formed in the late Three Kingdoms Period with the establishment of rice farming and the development of agriculture, and became settled during the Goryeo Dynasty. Bap and guk (soup) are always served together as a pair. Especially during times when rice was scarce and people had to eat coarse grains such as barley, guk became an essential element to make bap more palatable and easier to swallow.

The social and cultural developments of each era have made our dietary life even more diverse. During the Goryeo Dynasty, when Buddhism was the state religion, a vegetarian-based diet became mainstream. In the Joseon Dynasty, under the influence of Confucian culture, dietary etiquette and systems were strictly observed, and ceremonial foods for events such as weddings, funerals, and ancestral rites became systematized.

Additionally, essential fermented foods in Hansik such as ganjang (soy sauce), doenjang (soybean paste), and gochujang (red chili paste) are the result of ancestral wisdom developed over thousands of years of agricultural life to preserve food for extended periods. These fermented foods form the foundation of the unique flavors in Hansik.

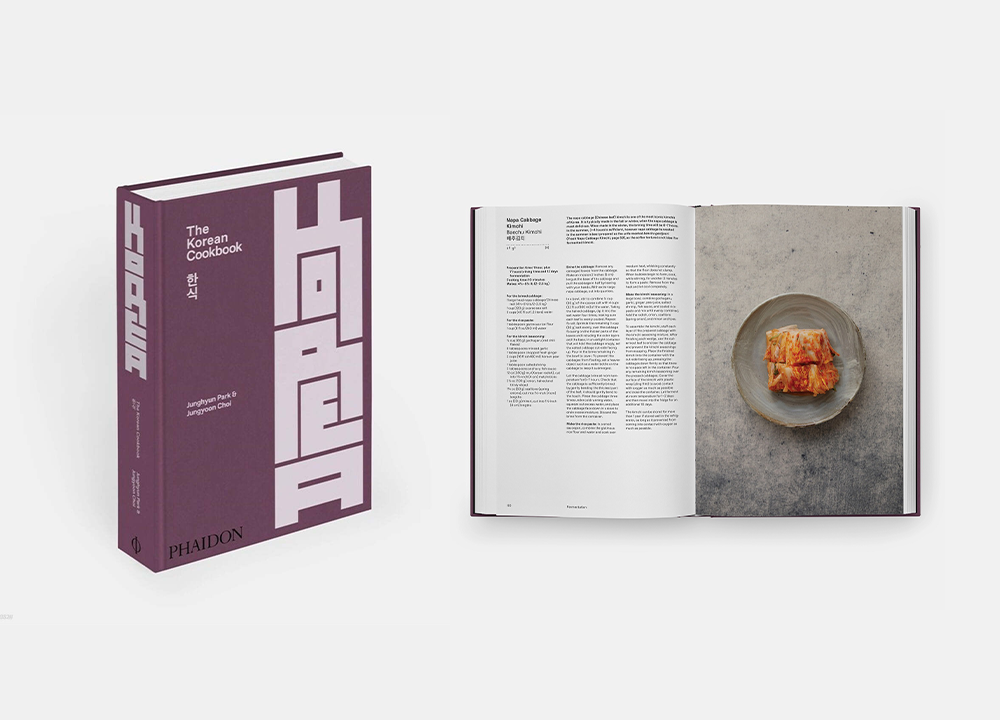

In October 2023, the book "Hansik”, published by renowned art book publisher Python, presents approximately 350 Hansik dishes in three chapters: 'Fermentation’, 'Bap (rice)’, and 'Banchan (side dishes)’. Co-authored by chefs Jungyoon Choi and Jung-hyun Park over a three-year period, this book introduces the uniqueness of Hansik enjoyed through a creative reinterpretation of various fermented foods and diverse ingredients, emphasizing a balanced and harmonious meal based on vegetal diet.

Particularly impressive is the way they describe banchan not as ’side-dishes‘, but as ’dishes to accompany rice’, and further elaborate by categorizing them into namul (salad) , muchim (marinated salad dishes), jjigae (stews), jeongol (hot pot dishes), jjim (steamed dishes), and gui (grilled dishes). As manifested in the extensive variety of Hansik cooking methods, Koreans have grown up enjoying meticulously prepared meals made of both common and precious ingredients and the taste and memories passed down from generation to generation sustain the lives of the people.

The Taste of Summer

Summer is the season that calls for food. With fresh vegetables and tangy, spicy-sweet seasoning mixed with rice and various ingredients, ssambap (leaf wraps and rice) is a summer delicacy that will stimulate your appetite during the heat of summer. The more you chew, the more you will enjoy the savory flavor that exudes. As a representative Hansik dish that brings various ingredients to be enjoyed in a harmonious combination, it is also a perfect zipbap menu that is better enjoyed in the company of family and friends.

In the summertime, crisp sangchussambap (lettuce wraps and rice) stimulate the taste buds. In the book "Why Do Koreans Eat Like This?" by Young-ha Joo, there appears a vivid passage describing how during the late Joseon Dynasty, scholar Yi Ok praised the taste of sangchussambap eaten immediately after the first summer rain, vividly depicting how to eat it.

"Spread your left hand wide like a copper tray, and with your right hand pick up thick and large lettuce leaves, laying two of them upside down on your palm (...). Pick up a piece of sliced scaled sardine hoe (raw fish) and after diping it in a bit of yellow mustard sauce, place it on top of the rice (...). With your right hand, tightly roll up both sides of the lettuce leaves, shaping them into a round ball like a lotus leaf. Now, open your mouth wide, revealing your gums and spreading your lips like a stretched bow." It is undeniably a mouth-watering description.

In the summer, the refreshing and clean taste of yeolmukimchi (young summer radish kimchi), which is stocked in every household's refrigerator, is also the best banchan to stimulate the appetite. While a great banchan in itself, yeolmukimchi can also be enjoyed as a topping for bibimguksu (spicy noodles), or mixed with a couple of spoonfuls of doenjangjjigae (soybean paste stew) to make a delicious yeolmubibimbap (young summer radish bibimbap). Thick, savory, and smooth kongguksu (noodles in cold soybean soup) makes a healthy meal, and the taste of borigulbi (barley-aged dried yellow croaker) dipped in tea also say, “It’s summer!”

Additionally, on hot days when your appetite is lost and energy levels drop, samgyetang (ginseng chicken soup) and jangeogui (grilled eel), both beloved as rejuvenating foods, are indispensable. Samgyetang, made by simmering fresh chicken with various medicinal herbs, and seasonal jangeogui, known for restoring energy, are rich in protein and essential amino acids, making them effective in revitalizing the body exhausted from the summer heat.

Korean cuisine pursues a healthy diet by emphasizing seasonal vegetable-based banchan (side dishes) that are harmoniously balanced with grains, fish, and meat. This coming summer, why not treat yourself to a refreshing zipbap meal?

References Encyclopedia of Korean Culture, Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture, <한식 인문학(Humanities of Hansik),' Dae-young Kwon, Health Letter, 2021>, <한국인은 왜 이렇게 먹을까?(Why Do Koreans Eat Like This?)' Young-ha Joo, Humanist, 2018>